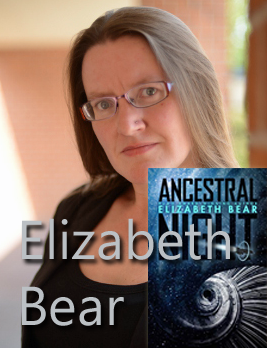

Elizabeth Bear is the author of “dozens of novels; over a hundred short stories; and a number of essays, nonfiction, and opinion pieces” and has won numerous awards including the Campbell, Hugo, Locus, and Sturgeon awards.

By Ernest Lilley

Ernest Lilley: You’ve written a significant (something of an understatement) amount of both fantasy and science fiction, can you talk about the difference in how you have to approach them? Does the technology in fantasy have to be as consistent as in science fiction?

Elizabeth Bear: I actually approach them in exactly the same way, in terms of consistency of worldbuilding. All that’s different is the foundation of the rules that the universe works by.

Fantasy is in no way less rigorous than science fiction, nor is science fiction necessarily more rigorous than fantasy. Certainly, there are examples of both that don’t have consistent physical laws or rigorous causality.

I’d be tempted to say that in fantasy, one of the central metaphors is that human desire and will is a powerful enough force to change the actual structure of the universe, but there’s plenty of science fiction that seems to revolve around the idea that just wanting something with all your heart is enough to get it.

But for me, in my work, that’s the dividing line: fantasy is where human will (magic) is an energy source with physical manifestations.

EL: After I read Ancestral Night, I went back and read your first novel, Hammered (2005) for which you won a Locus Best First Novel award (2006). Belated congratulations on that, btw. I thought they had some common elements (the feel of virtual flight, salvaging alien craft, the relationship between Maker/Feyman). I thought Hammered might be backstory for Ancestral Night. What do you think about that?

Elizabeth Bear: It’s a delightful thought, but I don’t think that’s possible. (People have also speculated that White Space is related to In the House of Aryaman a Lonely Signal Burns and other works in that future, and unfortunately that’s also not possible. I do use the term rightminding in several unrelated works of fiction, and archinformist also pops up in Undertow, but hey—I like writing about neurology, and once you’ve got a clever coinage, I say never let it go.)

The Earth in the Wetwired trilogy is not in nearly as much jeopardy of a major extinction event as the Earth in the backstory for the White Space books, and there’s no trace of a bunch of technologies that appear in the first series in the second one. The White Space books are, however, related to the Jacob’s Ladder books in that they take place in the same universe, about 200 years later.

EL: Back in 2011 you did a Lightspeed interview (It’s a great interview, we’re linking to it) where they said in the preamble, “She puts the reader to work, giving nothing away easily.“ I found that true of Hammered, but Ancestral Night was so full of big ideas that the main character often seemed distracted from the story by the need to explain them. It’s a grand tradition in SF to make the reader discover the shape of the story universe by putting clues together, but not so much here. Why?

Elizabeth Bear: Different first-person narrators are going to have different voices and approaches to storytelling. And to be honest, I’ve seen at least one review that considered this book pretty opaque on how the universe worked, so I guess your mileage may vary.

The discursive, opinionated, philosophizing first-person narrator is a tradition in space opera—anybody who claims otherwise probably hasn’t read any Heinlein, who memorably peppered some of his books with what were essentially bullet point lists of his protagonist’s aphorisms for how to be a Proper Human!

It’s funny you should ask about the level of exposition in the book, though, as the editorial process with my UK and US editors involved a great deal of taking exposition out and putting different exposition in, to fit both of their requirements.

EL: Throughout Ancestral Night you have a number of discussions of polity, ethics, and personal philosophy. Haimey Dz, your main character, defends her society’s practices of suborning the individual for the collective good, while her opponent, the bad girl pirate Fairweather is an unabashed egoist. Here altruism wins over egoism, although the whole “rightminding” thing is a bit cringeworthy.

Elizabeth Bear: Do you think it’s cringe-worthy? That’s interesting. How do you feel about using psychoactive drugs and therapy to treat trauma and mental illness? Do you feel it’s responsible for somebody with a mental illness that is potentially harmful to themselves or those around them to leave it untreated? What if the definition of what a mental illness is shifts over time, as cultures change?

Do you think that any set of cultural rules and considerations that puts the group over the individual is cringeworthy?

Or are you talking about the Judiciary personality reconstruction discussed in the book? In that case, I would ask you which is more unethical as a consequence for terrorism: allowing a violent criminal to choose to submit to a personality reconstruction that makes them safe to release into society where they can be a productive member, or subjecting them to lifelong incarceration, possibly in solitary confinement, at taxpayer expense–or execution.

My background is in anthropology and English critical theory, and I admit this has trained me to reserve judgment. I try to be aware of my own bias and ethnocentrism as to what an appropriate level of personal freedom versus social responsibility is, and it seems to me that there are a lot of different answers to that conundrum among societies in the world today.

Also, that it’s a gendered question, as women in the society I live in are expected to make far more personal sacrifices for the common good (of their families, of their communities) than men are.

I think there are, in general, benefits and drawbacks to most social structures. However, and more importantly, many of our current existential problems as a species stem from over-competition, overconsumption, and an inability to project the results of our current actions adequately into the future.

EL: Will you give the pirate (Freeport) point of view its day in upcoming books?

Elizabeth Bear: As for the Freeporters and their opinions–I don’t write didactic novels. I write novels in which people with different opinions generally get to air them—I hope fairly.

The Synarche is by no means a perfect society, but it’s a society in which there is a lot less suffering and privation than our current society. Nobody goes without food, shelter, or healthcare; freedom of movement and thought are protected; nobody needs to suffer through meaningless, grinding, physically incapacitating work just to survive.

An obligation to social service is a pain in the ass, of course, but so is jury duty, or the obligatory military service in a state such as Israel. And is it actually worse to be required to serve a term in office because you’re qualified than for the population as a whole to have to deal with corrupt career politicians and/or oligarchs as a matter of course?

Also, I do think the Freeport Republic—the “pirates”—gets a fair shake as to their point of view in THIS book, through the personas of Farweather and Niyara–and frankly, you can find their point of view in every self-help book currently published for Wall Street tycoons. There’s not a provocative speculative novel to be written about the economic system we actually already live under.

EL: Within our lifetimes we’ll get to see strong AIs that can do anything we can do better, even simulating personhood. When do AIs like your character Singer, get to be considered people?

Elizabeth Bear: Will we? People have been saying so for fifty years now. I’m personally withholding judgment as to whether a strong AI is on the horizon, and whether a real one would be anything we’d recognize as a “human” personality. In fact, there’s considerable disagreement as to what constitutes consciousness, if consciousness even exists or if it’s a neurological illusion, and whether it’s useful at all or a sort of cognitive dewclaw.

But that’s the real world and not fiction.

Singer is definitely a person, just as Dust in the eponymous book is a person (a fairly terrible one, though he has his reasons) and the Feynman AI in Hammered is a person. The fact that the Feynman AI is a fugitive and that Singer carries a crushing debt from his creation probably gives you an idea of how fairly I suspect we will treat our electronic children, should we ever manage to create any.

Speaking as somebody who paid off her student loans at the age of 45, I feel I can speak with some authority—or at least sympathy–on the burdens of obligation we already put on our children as a means of societal constraint. If you enter adulthood with tens of thousands of dollars a year in debt payments, that precludes seeking employment in a creative field where it may take a decade to get established, or starting your own business, or basically anything that doesn’t generate substantial income immediately.

The people who have created the society in Ancestral Night are trying to be more fair—but they don’t always succeed, obviously.

And that fairness comes at some cost.

EL: You continue to be one of the most prolific writers in SF/F, while managing to keep up the quality and new storylines. So, two questions – what’s your writing day like, and where do your ideas come from?

Elizabeth Bear: My writing day varies wildly, unfortunately, because travel and appearances and shifting deadlines and social obligations and trying to get outside to exercise at the time of day when the temperature is most convivial (Not first thing in the morning in winter, not at the peak of heat and sun in summer) get in the way.

Ideally, I like to get up in the morning and work for a solid four hours without interruptions. Then I take a break, eat something, and deal with administrative stuff. Toward the end of a long work, I get very eager to be finished—and the creative work becomes easier, because the pieces are already on the table and arranged by color, so to speak, and I just have to slot them into the puzzle in the correct and pleasing order—so I often write eight hours a day at that point. (Sometimes more.)

That’s not terribly healthy or good for my body, though, so I try to avoid it.

I used to be very disciplined about working as much as possible, and I discovered both that burnout is a real thing, and that creative work is exhausting and that I didn’t get much good work done after the first few hours anyway, so I was just wasting time when I could have been recharging or spending time with my family or cleaning the kitchen so it’s not a crunchy-floored cesspit!

Basically, a lot of it is just showing up and doing the work and trusting that you will get to the end somehow.

As for ideas, I go out in the back yard with a glass jar with holes punched in the lid, and turn over rocks until I find one. Then I grab it and pop it in the jar until I need to use it!

EL: Sadly, we lost Ian Banks a few years back, but gladly there are other folks out there writing excellent space opera, yourself included. Um, who are they again? Whose influence do we see in Ancestral Night?

Elizabeth Bear: Banks is a huge loss, obviously, but C.J. Cherryh is still with us! I think she, James White, Octavia Butler, and Andre Norton were probably the strongest influences on Ancestral Night, though of course, the Synarche grew out of my taking a long look at governmental structures like the Culture and the Federation and asking myself “So how would that actually work?”

Currently writing—well, there’s a lot of it! The next ones on my to-read pile are probably Max Gladstone’s Empress of Forever and Alex White’s A Big Ship at the Edge of the Universe. Recently, I have enjoyed Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit, Aliette de Bodard’s The Tea Master and the Detective, R.S.A. Garcia’s Lex Talionis, and Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire.

EL: Oh, and while I’m at it, what do you think of the Expanse novels. It seems like Naomi Ngata and Haimey Dz would find plenty to talk about.

Elizabeth Bear: I’ve only read the first one, so I’m way behind. I’m afraid that my reading tends toward the broad rather than deep currently, and I don’t often have the time for long series.

Maybe I’ll catch up when I retire!

EL: How long do we have to wait for Haimey, Conner, and Singer to return, and what will they be up to in the next Whitespace book?

Elizabeth Bear: Haimey, Connla, and Singer will not be returning in the next White Space book, I’m afraid. It’s an almost entirely new cast of characters, as my intent here is to write as many stand-alone novels set in the same universe as my readers and publishers will let me get away with.

A problem of series novels is that if you give a character a really satisfying arc and a lot of personal change over the course of a novel… how do you deal with that character’s story after? You can press a giant reset button, obviously, and make them start over… but that’s frustrating. You can start with an idealized character and make the story entirely about how they overcome external obstacles, but I’m generally not good at writing that kind of narrative. You can start with a very young character with a lot of growing to do, which is my strategy in the Karen Memory books.

Or you can try to make the entire society the central narrative, as Ian Banks does in the Culture novels and as Cherryh does in her Alliance-Union novels.

That last one is what I’m aiming for here! Perhaps there’s a little egotism in structuring one’s series after two of the best-known space opera universes around, but as Farweather would say, why think small?

Other Sources for More on Eizabeth Bear:

- Author Home Page: https://www.elizabethbear.com/

- Author Twitter Page: https://twitter.com/matociquala

- Wikipedia Entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Bear

- Author’s Goodreads Page: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/108173.Elizabeth_Bear

- Goodreads Interview (Elizabeth Bear’s Favorite Steampunk): https://www.goodreads.com/interviews/show/1007.Elizabeth_Bear

- Macmillan (Publisher) Author Page: https://us.macmillan.com/author/elizabethbear/

- Locus Online Interview Excerpts: https://www.locusmag.com/2006/Issues/04Bear.html

- AbeBooks: Elizabeth Bear – AbeBooks.com: https://www.abebooks.com/docs/ScienceFiction/elizabeth-bear.shtml

- Lightspeed Magazine Interview: http://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/nonfiction/feature-interview-elizabeth-bear/

- Clare3lsworld Interview: http://clarkesworldmagazine.com/bear_interview/

- Free Speculative Fiction Online: https://www.freesfonline.de/authors/Elizabeth_Bear.html

- Tideline (short story): http://will.tip.dhappy.org/blog/Porn%20Recommender/…/book/by/Elizabeth%20Bear/Tideline/Elizabeth%20Bear%20-%20Tideline.html

- 2008 Hugo Short Story Winner: Shoggoths in Bloom https://web.archive.org/web/20150217033537/http://www.asimovs.com/_issue_0803/shoggoths.shtml

Books by Elizabeth Bear Reviewed on SFRevu:

- Ancestral Night

- The Stone in the Skull

- An Apprentice to Elves

- Steles of the Sky

- Book of Iron

- The White City

- Bone and Jewel Creatures

- By the Mountain Bound

- All the Windwracked Stars

- Hell and Earth

- Ink and Steel

- Dust

- Undertow

- Whiskey and Water

- The Chains That You Refuse

- Hammered