Daryl Gregory has been cranking out some terrific fiction. He first popped onto our radar with last year’s Afterparty, then again with the Nebula Award nomination(1) for his Novella: We Are All Completely Fine, which meant we had to read the prequel novel, Harrison Squared, that came out this March. And then, we had some questions. Fortunately, he had time to find us some answers.

Daryl Gregory has been cranking out some terrific fiction. He first popped onto our radar with last year’s Afterparty, then again with the Nebula Award nomination(1) for his Novella: We Are All Completely Fine, which meant we had to read the prequel novel, Harrison Squared, that came out this March. And then, we had some questions. Fortunately, he had time to find us some answers.

SFRevu: Your novella, We Are All Completely Fine, came out in August 2014 from Tachyon, but Harrison Squared, its prequel, or first of its prequels, just came out in late March 2015 from Tor. Now, that doesn’t seem like quite enough time to have written WAACF, then decide to write a novel to set it up, so how did that happen, anyway?

Daryl Gregory: It happened in the most complicated way possible. I wrote the first draft of Harrison Squared as a middle-grade adventure novel, intending to write something light and fun with as much banter as possible. My idea of light and fun, however, was out of step with middle grade editors. Several of them said that what I’d written was way too scary for little kids. (I don’t think this is true. I loved gruesome stuff when I was ten. But hey, that’s the market.)

I was ready to set aside the book as an experiment, but it did start me thinking about what kind of PTSD a grown-up Harrison would have to cope with. And what about all those sole survivors of horror novels and movies? Surely they needed a lot of therapy. Jacob Weisman of Tachyon had been after to me to write a novella for him, so I pitched him the idea of a therapy group made up of final girls and last men standing. He thought it was a hilarious idea. I kept trying to explain that it wasn’t funny. We still argue about whether the novella is a comedy. I think we’ve compromised on “ultra-dark comedy.”

While I was writing the novella, Tor offered to buy Harrison Squared, but they were interested in YA, not middle grade, and asked if I’d be willing to change it. I said, if you’re willing to pay me, I’m interested. But this actually solved my scariness problem for me. An older protagonist, and therefore older readers, would be able to handle the creepy stuff, and allow me to spend more time with the monsters, which is always my favorite part of horror stories.

While I was writing the novella, Tor offered to buy Harrison Squared, but they were interested in YA, not middle grade, and asked if I’d be willing to change it. I said, if you’re willing to pay me, I’m interested. But this actually solved my scariness problem for me. An older protagonist, and therefore older readers, would be able to handle the creepy stuff, and allow me to spend more time with the monsters, which is always my favorite part of horror stories.

So, as soon as I finished WAACF, I rewrote Harrison Squared from scratch, using that first draft as a kind of detailed outline that was missing some of the story. But because I now had written the adult Harrison, that changed how I wrote him as a kid. There’s still a big gap between the boy he was and the man he becomes—but now I know what that arc is.

SFRevu: The setting in WAACF is a therapy group for survivors of supernatural horror, though at the outset its members don’t know that they’re connected. You did an excellent job of capturing the personalities and tensions crop up in therapy. How much of yourself are you channeling here? Which is probably just beating around the bush to ask if you’re as pissed off as Harrison. It’s OK. This is a safe space and nobody’s judging. Mostly.

SFRevu: The setting in WAACF is a therapy group for survivors of supernatural horror, though at the outset its members don’t know that they’re connected. You did an excellent job of capturing the personalities and tensions crop up in therapy. How much of yourself are you channeling here? Which is probably just beating around the bush to ask if you’re as pissed off as Harrison. It’s OK. This is a safe space and nobody’s judging. Mostly.

Daryl: When you’re writing this kind of ensemble piece, it’s your job to put yourself in each person’s shoes. So some of it comes from me, but most of it is imagination. It’s acting. I start with the person’s situation, and then think about how their body feels, and how they’d filter the information they’re getting.

In the group scenes, I would do a sort of round-robin of mental states. A character would speak, and I’d imagine how each character would respond, verbally or physically. Then you try to figure out if the point of view character in that scene would notice these reactions. Somebody who’s very empathetic would pick up on many of them, but someone more oblivious — or distracted by their own issues– would miss them.

SFRevu: In Harrison Squared the teens face a string of horrific events, but they manage to live pretty normal lives regardless, falling back on humor, some more deadpan than others, to lighten things up. Do you think teens process tragedy differently than adults?

Daryl: Not as much as adults might think. A teenager might not have the life experience to cope with tragedy–but many adults don’t, either. I do think that adults are more aware of how they’re supposed to process tragedy, but that can cause more problems than it solves.

Anyone who’s been to a funeral knows that hilarious things can happen. People crack jokes even in awful circumstances. Horror and hilarity are a hair’s breadth away from each other. (That’s a lot of H’s.) I don’t trust a novel or movie in which people don’t ever laugh. That just means that the characters have not been fully imagined.

SFRevu: I gather you recently got back from your Harrison Squared Tour. Any interesting experiences from the road? How did this tour differ from the one for Afterparty? Were the audiences as different as the book, or as similar as your themes?

Daryl: If something really interesting happens on tour, it’s probably something horrible. I’m happy to report that the trip itself was pretty low key. It was great meeting people who’ve read my stuff, and really great to meet indie bookstore owners who are excited about the novel and are willing to hand-sell it to customers after I’m gone.

As for the event itself, I’m just happy when anybody shows up to see me. I’d rather do comedy than read from the book, so I always get to the Q&A section as quickly as possible. I provide the questions. I hand them out on notecards, and then if the questions are too personal, I don’t answer them.

SFRevu: You’ve now left Harrison hanging at two different points in his life. I’m sure I’m not alone in wanting to find out where he goes after WAACF, but before he even gets there he’ll have to finish up the business in Dunnsmouth you’ve started him on in Harrison Squared. That’s a lot of writing. Did you know what you were letting yourself in for?

Daryl: I really didn’t think this through. I usually write standalone novels, and there’s a certain freedom in saying everything you have to say on a subject or character, then moving on. But I have to admit I’ve been a little jealous of writers like Michael Moorcock and Kim Newman who built a fictive universe, with characters they could return to at different points in their lives. Chris Roberson built an entire family tree of characters he can pull from at any time!

SFRevu: Since you’re e no stranger to manga and comics, I’m sure you’ve thought about making Harrison Squared into a graphic novel. Any chance of that? And speaking of other media, any nibbles on a movie, or is it two soon?

Daryl: Harrison Squared might make a good graphic novel, because of the monsters. Or maybe not. Usually when I put on my comics hat, I think of different stories that depend on the visuals.

As for movies, well, funny you should ask. People are always curious about movies and TV, and I always try not to get excited when something gets optioned. My standard explanation is: “Someone hands you an envelope of cash and a puppy. The puppy has a 99% chance of dying in twelve months. This is what’s called a movie option.”

But it looks like one of the puppies has a much better chance of living than usual. Right after you sent me these questions, the SyFy channel announced that they’d gotten Wes Craven to write the script and direct the pilot for a show adapted from We Are All Completely Fine. I’m looking forward to seeing what he does with that.

This is the first thing that’s gotten this far. Darren Aronofsky optioned my first novel, Pandemonium, to make into a TV show, and I would have loved to see that. An HBO producer is currently trying to create a show around Afterparty, but it’s in the very early stages. But until one of these projects actually gets to the pilot stage, I won’t grow attached to the puppies.

SFRevu: Taking it for granted that you’ve read Lovecraft, Dracula, and other horror classics, could you tell us a bit about what you read as a young adult yourself, and some important books or authors in your life as a reader and writer?

Daryl: Oh, I gravitated toward the weird stuff immediately, and it never wore off. I learned to read on comics, and Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were the gods of my youth. Then I discovered science fiction. I read everything I could get my hands on, but I was particularly blown away by Roger Zelazny and Gene Wolfe. As I got older, I kept returning to the books of Philip K. Dick, and he’s continued to influence my books. I included PKD as a character in my first novel, and Afterparty owes a lot to Valis(2).

SFRevu: Back in 1988 you attended the Clarion workshop where you wrote “In the Wheels,” your first published story. Before that you taught English. Now that you’ve got a lot more than one story to your credit, are you giving any writing workshops?

Daryl: I loved teaching high school. What I didn’t love were all the administrative headaches and the long hours — I got almost no writing done in those years, and going to Clarion the summer after my first year of teaching convinced me I needed a new life plan. So, I always say yes when I’m asked to teach. I’ve done a few workshops, and in June I’ll be teaching a day-long workshop at the Locus Awards Weekend(3). If anybody wants to see my slides and material, I post them for free up on my website(4).

SFRevu: Afterparty, your recent novel about a drug that supercharges the regions of the brain that give rise to a feeling of something like divine presence, was terrific. I’d call it Ken Keasy meets William Gibson, with the bonus of your writing. What inspired you to write it? And here’s an odd thought; what would happen if you gave the drug to a dog…or even a cat?

Daryl: I’m pretty sure my dog already thinks I’m a god. If you gave the drug to a cat, they would probably imagine themselves, only larger.

I’d been wanting to write a novel focused on neuroscience and pharmacology for years. Many of my short stories were about consciousness, the origin of religious feelings, and the illusion of free will, and several featured designer drugs, but I never could figure out how to make a novel-length story out of those ideas.

Meanwhile, I’d been reading a lot of crime novels, especially the books of Lawrence Bloch and Elmore Leonard, and I wanted to write a novel with that kind of velocity. So finally I struck upon the idea of writing a crime novel about neuroscience, big pharma, and imaginary angels, and making it a “road” novel that moved from Toronto to New Mexico. The trick was to discuss all my favorite ideas (like the illusion of the self) while not slowing down the plot. Fortunately, on a road story, you have time for smart characters to talk to each other about this kind of thing.

SFRevu: What are you thinking about besides Harrison and his friends? Are you making time for other works?

Daryl: I’m working on a long novel about a family of not-very-powerful psychics. I’m only halfway done, but I’ll spill more details later!

SFRevu: WAACF is a Nebula Awards nominee, so is there any chance we’ll see you in Chicago this June?

Daryl: I’ll be there with bells on. Chicago’s my home town, and every time I cross the Illinois state line I start salivating for Italian beef sandwiches and stuffed pizza.

SFRevu: We’re looking forward to that. Thanks for all the great answers, and best wishes on the Nebula.

Links / References

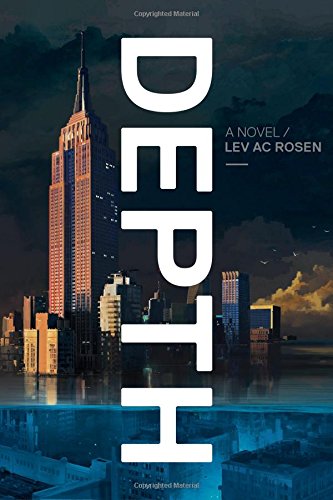

Depth by Lev AC Rosen

Depth by Lev AC Rosen