Set 125 years from now, Annalee Newitz’s debut novel comes at the question of property from two angles: slavery (both robotic and human), and intellectual property. It does so through the voices of its main characters, Judith, aka Captain “Jack” Chen, a pharmaceutical researcher turned pirate who clones high-priced drugs to distribute them to those who have more need than means, and a freshly-activated bot named Paladin, designed for security work for its owners, work like tracking down pharma-pirates.

Set 125 years from now, Annalee Newitz’s debut novel comes at the question of property from two angles: slavery (both robotic and human), and intellectual property. It does so through the voices of its main characters, Judith, aka Captain “Jack” Chen, a pharmaceutical researcher turned pirate who clones high-priced drugs to distribute them to those who have more need than means, and a freshly-activated bot named Paladin, designed for security work for its owners, work like tracking down pharma-pirates.

Paladin is sent, along with Eliasz, its human partner/handler, to stop Jack’s piracy, so it comes as no surprise that the two are on a collision course as Paladin and Eliasz roll up Jack’s network with bloody determination.

Jack is on a mission as well – the latest drug she reverse-engineered is killing people. Called Zacuity, the drug focuses your attention on whatever task you’re doing while you take it and gives you a dopamine hit of good feelings while you’re at it. The story is more complex than that, and the bio-tech the author leverages holds up nicely, but feel free to just enjoy the plot. Given under controlled circumstances in regulated doses, Zacuity makes you a devoted employee (the kind Silicon Valley dreams about).

In order to finance her philanthropy, Jack sold a large batch to her underground connections and weird obsessive behavior is cropping up among users. First a student that won’t stop doing homework, then a man who can’t stop painting his home, then more. Every day more people are dragged into emergency rooms exhausted, dehydrated, and desperate to get back to what they were doing…even if, as it often does, kills them.

Jack doesn’t see this as her fault, since she cloned the drug exactly as it was designed. To her, it means that the pharmaceutical company intended for the drug to be addictive, and managed to hide the drug’s dangers through its Phase 1 (human trials) testing. As an ethical pirate, Jack accepts responsibility for the damage the bootleg version is causing and sets out to stop its distribution, find a way to reverse its effects, and blow the whistle on the original drug.

Before Paladin kills her and everyone she knows.

The author meticulously researched the tech in this book, especially the neuroscience, but she made some choices, particularly with regard to Paladin’s mental abilities, that made me cringe. When Eliasz is confronted by Paladin about his physical arousal around the bot, he insists “I’m not a faggot!'” This serves to open up discussions about robot’s gender and sexuality, but Paladin spends an ungodly amount of time and research trying to decode the comment.

The author meticulously researched the tech in this book, especially the neuroscience, but she made some choices, particularly with regard to Paladin’s mental abilities, that made me cringe. When Eliasz is confronted by Paladin about his physical arousal around the bot, he insists “I’m not a faggot!'” This serves to open up discussions about robot’s gender and sexuality, but Paladin spends an ungodly amount of time and research trying to decode the comment.

Then there’s the business with face recognition, an AI problem that’s been largely solved and one which, given the processing and number sensory equipment given the bot, is trivial to affect. At the outset, Paladin does well at face recognition, because it’s got a brain…an actual human brain, donated (posthumously) by a soldier and used like a graphics card to do certain types of pattern recognition, including faces. The bot has its own AI brain, which does all the heavy lifting, with no access to the “file system” of the deceased human brain it’s carrying around in its midsection, so what’s the point? Another bot explains that it’s marketing to make humans more comfortable dealing with AI’s, which makes it a useful plot device, especially in Paladin’s relationship with Eliasz.

Character-wise, this isn’t really Jack’s book. Sure, Jack wanders through the landscape on a quest, and we spend a lot of time in her backstory, from farm-girl to pharma-pirate, but she’s largely there to provide action and adventure for the reader, and a goal for Paladin, whose coming-of-age story is the real core of the book. Ultimately, the two collide, but for Jack, it’s a near-miss rather than a moment of clarity, while Paladin doesn’t really need the event to further its journey of self.

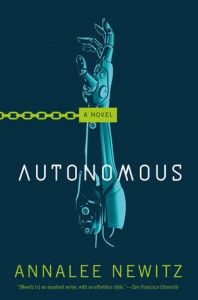

The book’s jacket invokes the twin deities of cyberpunk, William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, who say nice things about the book. Nice is appropriate, but no one should go overboard in their praise. Autonomous is set in a landscape pioneered by Gibson, Stephenson, and others, with economic free zones and evil corporations even if the landscape is reskinned with biotech. That pharma-tech will be a major economic player isn’t news to anyone currently alive. James Blish’s Cities in Flight (A Life for the Stars (1962)) talked about using pharmaceuticals as currency. Addicting workers to their jobs and the ultimate power of corporations would have been appealing to both Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth, who together laid the groundwork for both in The Space Merchants (1952).

Newitz does bring some interesting ideas to the table, including the notion that granting artificial persons human rights might lead to indenture for both robots and humans. It would be extraordinary if there were not a lot of good ideas in here, considering that the author is a prominent editor and science/culture journalist.

Newitz has two other books in the works, one a time-travel adventure with political activists, and the other a non-fiction about abandoned cities and what the causes behind their demise (Note: Ms. Newitz does not like it when people suggest Detroit for the book, as it is not abandoned).

In the end, Autonomous is good science fiction and a good book, but not a brilliant example of either. The importance of this book is more about the character development of the author than the characters in the story. Annalee was Editor-in-Chief of the tech culture site IO9 until it merged into Gizmodo, and is currently Tech Culture Editor at Ars Technica. Although she has written several nonfiction works, Autonomous marks her debut as a novelist and the change from the passive voice of a journalist to the active one of a futurist.

If you like this book, or want more on similar themes, I recommend Daryl Gregory’s novel Afterparty, also pharma-punk, but with much better mind expansion.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01N4P14CI/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1